The language of quality: four metaphors for Quality Assurance

The Educationalist. By Alexandra Mihai

Welcome to a new issue of “The Educationalist”! This week I am happy to have another special guest, Matthijs Krooi, who kindly shares his insights on the very relevant topic of Quality Assurance in Higher Education. While this topic mostly resonates with those involved in HE management, if we come to think about it a bit deeper we realise that it is connected with many of the things we do as educators, students or staff. Matthijs is providing us with some food for thought and some resources on the topic, which I hope you’ll find useful. Wishing you happy reading and a good weekend.

Quality assurance has the potential to support universities in becoming true learning organisations that encourage experimentation and reflective dialogue. This might be surprising to read, because while all educators in Higher Education institutions are confronted with quality assurance in some shape or form, few are really fond of it. Some would even describe it as a rather terrifying experience (more about this below). However, I would say that there is a lot to love about quality assurance if you look beyond the standards, forms and manuals, and find that it can actually help universities and educators. Of course, I know that many institutions are still struggling with this. But I also know from my experience as a practitioner and researcher that the field is evolving quickly, and that the key towards positive change is to focus on imagination.

A quick definition of Quality Assurance

There is not one fixed definition of quality assurance, but a fairly standard one is that it refers to all processes and initiatives that are deliberately carried out to design, evaluate and improve teaching and learning within an institution. While this sounds positive, it is difficult to achieve for many reasons, two of which I want to mention here:

A fundamental tension at the core of quality assurance is that we all want to provide high quality education, while we don’t have a universal definition of what “good education” really is. We do have some things to mitigate this uncertainty, such as proxies (e.g. student satisfaction, rankings), standards (e.g. constructive alignment), procedures (e.g. student surveys, participatory bodies) and relevant boundary conditions (teacher professional development, governance);

The second tension is that universities are just unbelievably complicated organisations: they tend to be large, hierarchical organisations, but at the same time also highly decentralised. While sharing the same logo, departments within the same university can function as wholly different silos. Academic staff have both teaching and research responsibilities, which often leads to conflicting priorities, especially if teaching isn’t recognised and rewarded by the organisation.

Four perspectives on Quality Assurance

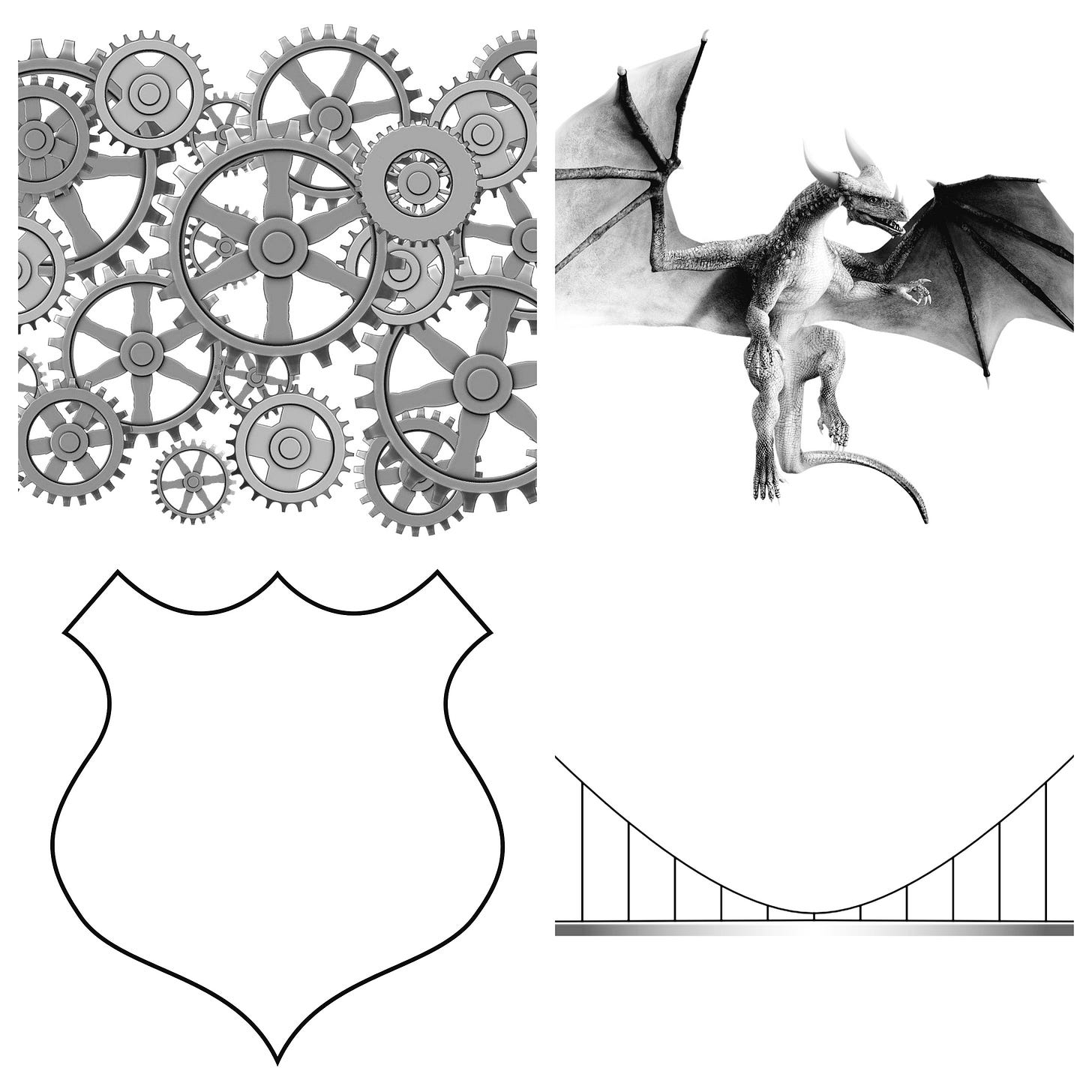

Because quality assurance has so many different manifestations, having a fixed definition is not very helpful. Instead, I want to offer different perspectives on QA, which you might find helpful in your specific circumstances. Metaphors can provide powerful images and function as lenses that put certain aspects of this complex topic into focus. Here are four metaphors for quality assurance:

1. The Bureaucratic Beast

One classic article on quality assurance is called Feeding the Beast or Improving Quality?, in which Jethro Newton describes quality assurance from the perspective of academics in a British university department. This article, and others like it, describe QA as a bureaucratic monster, that intrudes on personal and professional boundaries with arbitrary performance indicators or elaborate forms. The notion of the bureaucratic beast refers to the things you have to do in order to be accountable to some external force. It can indeed be demotivating, especially for intrinsically motivated educators, to do things because you simply have to. It is associated with forms, evidence and audits.

2. The Machine

The machine is the picture that is often evoked by institutional policy documents. This is the metaphor of choice for practitioners of Lean or Kaizen, and followers of Deming. Born out of industrial manufacturing, this mechanistic line of thinking is that if we design systematic, clean, step-by-step processes, we can rule out “waste”, and achieve a state of “continuous improvement”. And indeed it can be very helpful, but we always need to remind ourselves that reality is often messy: the focus on process often comes at the price of attention for the people who are reduced to being cogs in the machinery. Does the script that the machine prescribes really fulfil the needs and expectations of all stakeholders? Does it really contribute to quality? Do the indicators really indicate anything useful?

3. The Shield

One argument for quality assurance is that its language and mechanics can provide protection from external forces that threaten our autonomy (such as the governments that fund our endeavours). If we are able to convincingly define and describe what is “good” in terms that outsiders understand, we can be in control of our own education. Because quality can mean different things to different people, concepts like “constructive alignment” and “programmatic assessment” can give words and a logic to things that are otherwise hard to describe. Finding the right words and concepts (if sincere) helps to convey the notion that, yes, you really thought things through. The shield is associated with, and fortified by, reflection forms and action plans – not as a goal in themselves, but as meaningful support tools for reflection and accountability.

4. The Bridge

This is how I prefer to see the instruments of quality assurance: as building blocks that help forge connections between individuals, courses within a curriculum, organisational units, hierarchical layers, or even between institutions. It can help connect students to teachers via feedback and co-creation. It can help make knowledge and good practices in the organisation accessible, link educators to peers or coaches with the right expertise. It contributes to universities becoming learning organisations, for instance by facilitating connections between evaluations and educational developers, to learn from feedback and discuss improvements together. Or between groups of colleagues, to reinforce shared ownership and exchange.

These different perspectives are intended to make us rethink the manner in which we approach quality assurance. Few of us have the power to really ‘change the system’ into the perfect intentional quality machine, but perhaps a different way of looking can help to craft what is at hand into something useful. And perhaps it helps find the right words to plant some seeds for rethinking what is actually helpful for motivated educators and staff developers.

Some do’s and don’ts

DO: try to make most of the instruments that you are offered, focus on the aspects that are helpful;

DON’T: think standardised procedures are anything other than means toward an end;

DO: if you think something (e.g. a procedure, a form, a survey) doesn’t make sense, talk to quality assurance officers about what they think is the true intention or purpose;

DON’T: accept it when people have no other justification than “we always do it this way”.

And most importantly:

DO: engage in dialogue with others about what you consider quality in the context of your course, programme. Connectedness with others is a source of joy in itself, as well as a great resource.

Further resources

The book “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” (1976) is a philosophical novel written by Robert Pirsig. It is hard to do it justice in a short space, but what shines through for me is that it highlights the relationship between caring about something and the quality of that something – whether it is about motorcycles, human relations, or education.

The article Quality Literacy - Competencies for Quality Development in Education and e-Learning argues that quality development is a competence in itself that can be learned though practical activity, integrating certain knowledge, skills and attitudes. This line of thinking helped me to understand why some colleagues just get it, and others don’t.

While there is not (yet) a thriving blogosphere about quality assurance in Higher Education, I do like to recommend one fairly recent blog post about Learning from failure in higher education institutions. In the competitive environment of academia we tend to associate failure with shame and negative consequences, rather than engage with it as an opportunity for learning. This is not only important for ourselves as professionals, but for our students as well. Especially as we are currently having difficult conversations about study stress, performance, uncertainty, anxiety as barriers to learning.

Matthijs Krooi is senior policy advisor and lead auditor at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, as well as external PhD student at the Maastricht University (department of Educational Research and Development). His daily work and academic activities revolve around quality assurance of teaching and learning in Higher Education institutions. In particular his interest goes out to how organisations shape procedures and vice versa. You can follow Matthijs on Twitter or LinkedIn.