Welcome to a new issue of “The Educationalist”. This week I want to focus on a topic that is very relevant to the learning process and yet, all too often taken for granted and seldom discussed: knowledge management and the more specific online media literacy skills. As we put a lot of effort into designing and teaching our courses, we tend to assume that students already have these skills or can simply catch them “on the go”. Now when teaching and learning have moved online, this topic is more important than ever. Below you can read my thoughts on why training students to manage their information online and offline is a crucial part of their learning experience. I’ve also put together some ideas of practical exercises you can use in the classroom in order to train these skills. At the end I am adding a few resources you can refer to if you are interested in finding out more about this topic. Hope you find this useful and, as usual, I am looking forward to your comments and ideas.

Knowledge management: what and why?

What I refer to as “knowledge management” in this context goes beyond “information management”, including:

Finding sources;

Evaluating the quality and trustworthiness of the source and the information, as well as its relevance in the respective context;

Processing the information to answer specific needs;

Creating new knowledge using the gathered information;

Disseminating/ sharing the knowledge.

These skills are at the heart of the learning process for a variety of reasons. By training them throughout their studies, in a safe environment, students are:

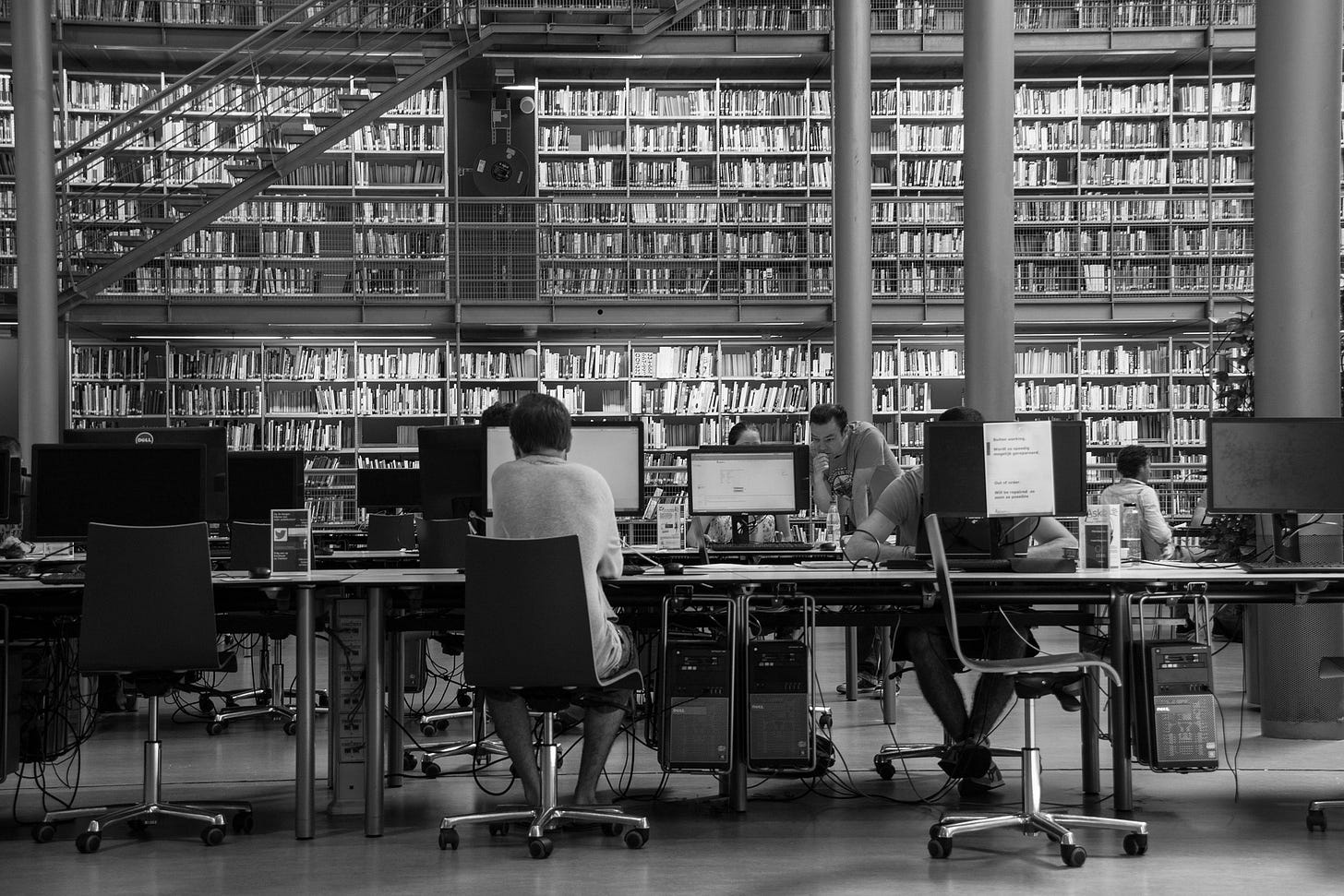

Learning to search for and deal with a variety of sources. It is all too easy nowadays to limit our search to the obvious information sources, mostly available online and easy to reach. Do send your students to the library and explain them why it is (still) very relevant to read books and to intentionally look for certain resources;

Learning to critically assess the information they come across- the importance of a critical mindset cannot be overestimated and there is no better moment to develop and train it than in the context of graduate programmes;

Learning how to store information in a structured and easily retrievable way- creating a personal knowledge management system supports students in their learning and in making sense of the professional world they are about to enter;

Learning how to use the information in the process of knowledge creation- everything from correctly referencing different pieces of information to building and defending an argument;

Learning what and how to share. Sharing has become common place today and it mostly happens semiautomatically, with a click. Each of us can play our small part in keeping the information landscape as clean as possible, simply by reading what we are about to share and giving a thought to why we are doing it.

Below you can find a few ideas of exercises that you can introduce in your syllabi with the aim of training the above mentioned skills; they vary from simpler to more complex tasks. At first sight they might not be at the core of your course but if you give it a try you will notice that they will enhance your students’ overall performance as well as the quality of their academic output:

Find your (re)sources (1). Instead of offering students all the reading materials for your course, make them part of the process and ask them to find a few resources for a specific class themselves. You can specify what types of resources you would like them to find (academic article, books, policy documents, websites, etc) and how many. You can ask them to reference the resources and briefly describe how they found them.

Find your (re)sources (2). Building on the previous exercise, you can ask students to add for each resource a paragraph on why they think it is relevant in the respective context (i.e. for that class) and, in some cases, how they checked whether the source is trustworthy. This exercise can be seen as an “annotated bibliography”. Both these exercises are important as they encourage students to intentionally search for relevant resources and not only rely on what you provide them with. This is a crucial skill, even (or especially) when it comes to very complex topics. After all, you will not always be there for them in the future to suggest the perfect article, and they will later be very grateful to you for this skill.

Recommend (re)sources. Ask students to recommend (re)sources to their peers. They should reference the pieces and write a brief recommendation on how they can be used in the context of the course or that specific class/ task.

Collective bibliography. Creating a wiki where everyone contributes with resources for the course. If you would like to build this exercise further you can ask students to take turns throughout the semester in curating this “collective bibliography”, making sure the items are correctly referenced, relevant and there is no duplication. This can be e very useful resource for you (as it showcases students’ diversity and it thus can include some items you would have otherwise not come across) and also for the students (you can even re-use it with future cohorts).

Peer review. You can connect this exercise with one of the previous ones. The main idea here is to ask students to comment on each other’s resources. As the selection of information sources is often very personal and linked to own values, it is important to learn how to engage is a well-reasoned and respectful manner with each other’s choice or resources.

Online media literacy

An important part of knowledge management nowadays takes place online. A lot of the information sources can be found online and this makes it important to train students to evaluate these sources in a very systematic and thorough way. Moreover, as we live in a “post-truth” era, students need to develop and maintain a critical mindset they can apply to what they read or watch online. We should not fall in the trap of thinking that if they are “digital natives” they will automatically be able to spot fake news or identify a website built for disinformation purposes.

Here are a few exercises that focus specifically on the online media and can complement the ones mentioned above:

Research a claim: Ask students to search online to verify a claim about a controversial topic;

Website reliability: Ask students to determine whether a website is trustworthy (read article on that below);

Social media video: Ask students to watch an online video and identify its strengths and weaknesses;

Claims on social media: Ask students to read a tweet and explain why it might or might not be a useful source of information;

Subscribing to online sources: Ask students to find an efficient way to manage their personal online media landscape (e.g: newsletters, RSS feeds).

Resources

If you want to read more about these topics I recommend the following resources:

Stanford History Education Group- Civic Online Reasoning: very useful resources on how to integrate knowledge management and online literacy skills in your curriculum;

Educating for Misunderstanding: How Approaches to Teaching Digital Literacy Make Students Susceptible to Scammers, Rogues, Bad Actors, and Hate Mongers: a study on how universities can do a better job helping students become discerning consumers of digital information;

The “Always Check” Approach to Online Literacy: some helpful hands-on tips on how to train yout students’ digital information literacy from Mike Caulfield;

Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning: a study by the Stanford History Education Group validating a set of assignments related to civic online reasoning;

The Challenge That's Bigger Than Fake News. Civic Reasoning in a Social Media Environment: some ideas on assignments related to online information literacy;

Helping Students Develop Critical Information Processing Skills: examples of activities to try with your students.

And an article that gives us some food for thought about how our brain works: “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. New discoveries about the human mind show the limitations of reason”, by Elizabeth Kolbert.